The Voice of Youth

My first taste of ‘activism’ was four years ago, when my friends and I gathered in front of the New Zealand Parliament, or fondly known as the Beehive, to participate in a ‘Free Palestine’ march.

Along with about a hundred people or less, we peacefully and in orderly fashion marched down Lambton Quay towards the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade building. I remember the policemen assisted in directing traffic as Lambton Quay was blocked off specifically for the march.

That image burned into my memory as it was a stark difference to images I’m used to back home. It didn’t take much for me to participate, just a yearning to show solidarity with the Palestinians and I was overwhelmed with the fact that we were not met with resistance from authorities.

But here, back in Malaysia, a simple act of solidarity could earn you some serious implications. Take for example the UKM four students – four political science students from Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia who were charged under the Universities and Colleges Act 1971 for being in the vicinity of the Hulu Selangor by-election last year and allegedly showing support, sympathy of opposition towards political parties.

Clause 15 of the act states that “No person, while he is a student of the University, shall be a member of, or shall in any manner associate with, any society, political party, trade union or any other organization, body or group of persons whatsoever, whether or not it is established under any law, whether it is in the University or outside the University, and whether it is in Malaysia or outside Malaysia, except as may be provided by or under the Constitution, or as may be approved in advance in writing by the Vice-Chancellor.” Clause 15 (3) further outlines the prohibition for any student to “express or do anything which may be construed as expressing support, sympathy or opposition to any political party or trade union or as expressing support or sympathy with any unlawful organization, body or group of persons.” This ominous law pretty much did the job pacifying our youths, to the extent that we compromise their freedom of thought and opinion.

Farhan is one youth that is undeterred by the act. “My first participation with the civil society was joining Chi Too’s Main Dengan Rakyat (Playing with the citizens) in 2008. It was just a bunch of people reclaiming public space and playing peoples’ games such as tag, konda kondi, sack race – games that we used to play as children.

“During foundation year, I would go out and wander around Kuala Lumpur on my own during weekends. I started reading alternative news and was exposed to the socio-political situation of Malaysia.

“I wasn’t happy with what I was seeing – citizens being discriminated against. So I helped out with Food Not Bombs and joined a humanitarian relief effort for mobile clinics in the rural areas. I realized what’s happening on the ground can be attributed to what’s lacking at the top.

“I would always go to the Annexe and got to know the scene there – events like Freedom Film Festival, or the talks and screenings that they regular organize and from there I got to know Frinjan,” said Farhan.

Frinjan, derived from the word ‘fringe’, is a voluntary collective of literary practitioners working to promote socio-political issues through the arts and literature.

“I see the art that Frinjan brings carries meaningful content. And with youths, we can’t use old methods like lectures and talks any more to attract their attention but we can use the arts, like theatre, music, poetry and writing to inject the socio-politic elements into our message.”

Through mingling with the civil society groups, I got to know some very passionate and dedicated youths, who believe in making a difference, by participating in movements and social projects and feel that voicing out their opinions is not a choice but a right. But it’s also disheartening to find that youths like Farhan are a precious few.

“Of course I think youths should be more involved but there’s that problem of ignorance. Not just plain ignorance, they are scared that action will be taken against them. We are constantly trying new things to get the youths involved, so we make the Frinjan scene ‘cool’ and appealing to them. But sometimes the ‘cool’ element can be detrimental to the cause itself. The cause will lose its meaning when everyone gets on board just because it’s cool to be different, but they are missing the point.”

The Malaysian civil society seems to be predominantly English-speaking, which can be a problem as it creates a barrier for the Malay speakers. Academicians and forums often use English as their mode of communication and automatically, alienate a large part of our youths. Unlike in Indonesia where books are translated into Bahasa Indonesia, our Malay-speaking youths have limited access to alternative knowledge – knowledge different from our one-dimensional education system.

Zul, Frinjan lead co-ordinator piped in; “The challenges we face are engagement and language. There is a stark difference between the English, Bahasa Melayu and the vernacular-educated. And then you have the East Malaysians with their own languages. If we want to attract a larger crowd we have to collaborate with groups who are English speakers. We’re also too urban-centric. If we take our cause outside of KL, we lose the connection with the locals there. We haven’t quite bridged that gap.”

There are many challenges that face our civil society, including the restrictive laws that govern social conduct, general complacency and a sort of distrust that exists among our society.

When one advocates causes such as human rights or even presenting the viewpoints of alternative history, it is easily met with resistance. We regress into our cocoons when faced with something we are not familiar with. Any issue deemed controversial or taboo gets muddled with politics.

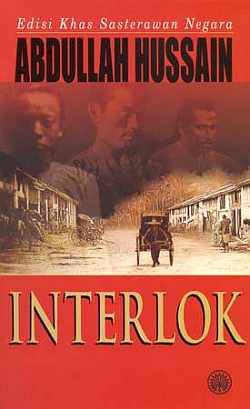

Issues that are fundamental concerns to the community such as Interlok or MyBalikPulau somehow found their way into political bickering. It is challenging to present different ideas to a society indoctrinated with one dominant ideology for a very long time.

“Youths don’t challenge each other via ideas, because in our schools, we don’t develop ideas of our own. Clearly, our education system is limited, but that is beyond our reach - that is the domain of the government and government policies. But what we can do is to work with our surroundings and be inclusive and make an effort to influence our peers and to use the language that they are most comfortable with,” shared Zul.

It is easier to assume the role of an armchair critic than to be an active citizen who is engaged with their community; who can think independently and are on the ground working towards building a strong civil society like the Frinjan group and their peers amidst the shackles and chains imposed on us. Their dedication and passion give us hope to a more vibrant and active civil society, and I believe that little by little, they will push their way through and become formidable pressure groups - the fifth estate - a crucial aspect of a democratic country which is long overdue.

Published, May 4th, 2011.

dipetik dari artikel asal di http://tapestrycolumn.tumblr.com/post/18063733771/the-voice-of-youth#notes